Few aspects of a professional’s career, other than technical expertise, have as much of an impact on individual success as those relating to handling clients. Of those, fee negotiation, i.e. the ability to be as comfortable negotiating with a client as on their behalf is probably the most challenging. This skill has become even more important over recent years as competition has become fiercer and clients have become more professional in their approach to sourcing professional services.

Given the importance of this skill it has always been striking that only a tiny fraction of professionals seems at ease negotiating with their clients. The natural talent that some have for this highlights the shortcomings of the rest. Given that almost all professionals are comfortable negotiating on behalf of their clients it suggests that the issues are of a personal or psychological, rather than technical nature.

So what is it about fee negotiations that make them so difficult for professionals to engage in? A number of factors have conspired to make this such a challenge:

Going global is a relatively new strategy in many professions (i.e. less than 20 years). The resultant growth in the size of firms and their need for a broader client base required professionals to be more active in the pursuit of new clients and business. The current generation of professionals responsible for leading relationships and fee negotiations have few role models.

At the same time clients have become more sophisticated in their demands on and use of external advisers. These demands included greater commercial understanding of clients’ needs and better “value for money” or at least transparency and predictability of costs.

Professionals are struggling with these challenges. Many firms and training bodies are still considering how to broaden their training programmes to include commercial topics. This in turn has meant that in the meantime many professionals still see themselves first and foremost as technical experts rather than as professional service providers who happen to have a technical expertise.

In addition to these “big picture” issues however there are a number of specific psychological drivers that make fee negotiation particularly challenging and which easily explain why otherwise highly competent individuals, avoid engaging in an activity that has significant potential benefits. Professionals who appear to be “born” fee negotiators seem to understand these drivers and have found ways to use them to their advantage.

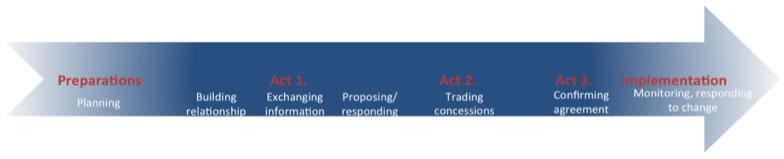

To help understand these drivers it is helpful to look at a typical negotiation (see diagram below). Almost all negotiations involve a preparation phase; three phases, also referred to as acts, in which the gap between two parties is established, narrowed and finally closed; and an implementation phase.

© Ori Wiener, MPSFG 2013

A multitude of psychological drivers operate in all of these phases. Recognising the most important ones for each phase and learning how to use them to one’s advantage or how to counter their influence should be a core element of any fee negotiation training programme.

Preparing and planning are crucial determinants for negotiation success. Drivers that affect how much and how well we prepare will have a disproportionately large impact on negotiation performance.

The psychological phenomena most relevant during the preparation phase are culture and ambition. Depending on our cultural origins, some of us will be more inclined to see negotiations as something “normal” or as something “alien”. Some of the most common reasons for not negotiating given during our negotiation programme include: “one does not talk about money”; “this is not what my job is about” and “I hate having to justify the value of our work”. All of these statements reflect a cultural perspective fairly standard for typical “Western” professionals. If not recognised it becomes easy to succumb to these biases and avoid fee negotiations or defer planning for a fee negotiation.

One of the most significant determinants of negotiation success is the ability to set ambitious and realistic targets. Our experience shows that most untrained negotiators fail to set themselves ambitious targets and needlessly leave money on the table. Applying a methodology for setting ambitious and realistic targets and supporting these through preparation is a key hall mark of an effective negotiator.

The level of psychological pressure experienced by most people rises dramatically when the protagonists meet at the negotiation table. Experienced and trained negotiators understand this and use it to their advantage. They also switch their focus depending on the stage the negotiation has reached.

Outstanding negotiators for example will focus during Act 1, when the parties first meet, on building trust so as to be able to extract as much information as possible from their counterparts. Such efforts don’t just aim to generate competitive advantage but will often help craft agreements that are of mutual benefit by increasing the total size of the pie to be divided. Furthermore, building trust early also encourages each side to make still greater efforts to find “win-win” solutions. Where there is an absence of trust, on the other hand, negotiations tend not to progress as well and the outcomes tend not to be as positive to either side.

Experienced negotiators make an effort to project their negotiating power at an early stage of a negotiation. This can be done in a number of ways typically applying the effects of a psychological phenomenon known as “loss aversion”. The best example is to tell their counterpart early one that one has alternatives, e.g. “one of your competitors is quoting…..” or that by not agreeing the other side will forgo a major benefit, e.g. “if you don’t agree you won’t get X”.

Another powerful influencing tactic used to great effect at this stage is “anchoring”. Most people evaluate a proposal or the outcome of a negotiation against a reference point set early in the negotiation. The side able to “throw out” its anchor first is typically in a stronger position. It is therefore usually an advantage to be the first to put a number on the table. Although professionals are usually invited to do so most professionals are reluctant and defensive rather than relishing in the opportunity. We see that professionals who are natural fee negotiators have a preference to go first or seize the opportunity when asked to do so by a client.

Experienced negotiators will also be on the lookout for any signs that indicate that their counterpart is not committed to their demands or opening position. The underlying psychology operating here is known as “cognitive dissonance”. Individuals reflect discomfort with a particular negotiation position either verbally or physically. Typical signs include evasive body language, hesitation, throat clearing, changes in voice pitch and a series of key words or phrases such as “in the region of”, “about” or “we were thinking of…..” With a bit of practice these signs are easy to pick up and furthermore, can be eliminated or minimised from one’s own behaviours.

One of the most dangerous pitfalls during Act 2, the stage at which mutual concessions are traded is the “reciprocity bias”. This powerful bias operates at several levels. People’s tendency to go for a “split the difference” approach can be exploited by sharp negotiators who raise their demands thus shifting the apparent mid-point in their favour. More insidiously however are techniques in which one party makes demands (that are not seriously meant) and then withdraws these, sometimes even unprompted. That party then goes on to demand a meaningful counter concession thereby applying maximum pressure on the other side to give up something valuable.

Although the closing act tends not to be as critical in a legal fee negotiation here too are a number of drivers that can be used effectively. These include a further application of “loss aversion”, as in “we are so close to an agreement, if you could just agree to ….., otherwise you won’t get….” Also effective at this stage are tactics such as “salami slicing” which work because of the effects of “framing”. By positioning extra demands as “minor” compared to the overall size of the deal, effective negotiators can squeeze out surprising amounts of additional value for themselves without risking the overall agreement.

The key issue with all of these influencing and negotiation techniques is that when recognised and understood they can be used to great effect or, if on the receiving end, their effects can be neutralised with relatively little effort. It is surprising how much more effective fee negotiators partners can become with a little practice and the right training.

Contact details:

ori.wiener@mollerpsfgcambridge.com

© Ori Wiener, MPSFG 2013